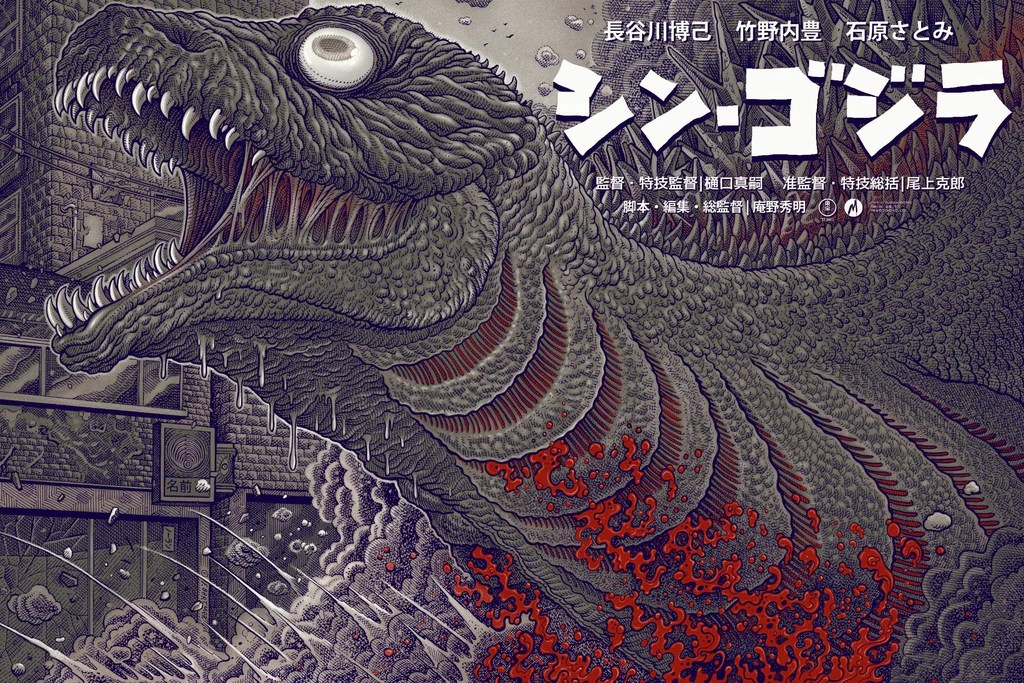

In the aftermath of Japan’s devastating 3.11 triple disaster–a massive earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown in 2011–the nation faced profound disillusionment with its government, industries, and people. Amidst this turmoil, the film Shin Godzilla, directed by Hideaki Anno and Shinji Higuchi, emerged as a powerful cinematic reflection on the nation’s resilience and cultural identity. Shin Godzilla can be seen as a modern-day embodiment of the original Godzilla (1954), which was a metaphorical response to the trauma of atomic bombings during World War II. Just as Godzilla (1954) was a displaced version of the atomic bomb, the 2016 iteration emerges as a response to the 3.11 nuclear disaster. Drawing upon various aspects of Japanese culture and society, the film paints a compelling narrative of redemption and hope in the face of seemingly insurmountable challenges.

In Shin Godzilla (2016), Anno ingeniously recreates the four stages of the triple disaster in its depiction of Godzilla’s attacks, highlighting the seismic shock, tsunami, efforts to cool nuclear reactors, and the subsequent struggle to contain radioactive fallout. This deliberate mirroring of real-world events allows the audience to process their trauma through the lens of the iconic colossal monster, serving as a form of cultural therapy (Mihic 89).

A key aspect that resonates with the Japanese audience is the film’s portrayal of Japanese technology as a savior. This theme of “Japanese technology saving the world” is a recurring motif in Japanese Godzilla films. In the original Godzilla (1954), American science was responsible for the monster’s creation, whereas Japanese science, spearheaded by the self-sacrificial Dr. Daisuke Serizawa and his discovery the “Oxygen Destroyer,” emerged as the ethical and responsible alternative (Mihic 92). Shin Godzilla takes this concept further by suggesting that Japanese technology can not only understand but also defeat the monstrous threat as the portrayal of the Japanese “Operation Yashiori” team of ragtags and outcasts led by Yaguchi and how they deciphered Godzilla’s biology to produce a blood coagulant and extremophile bacteria is a testament to Japanese scientific prowess (Mihic 94). This representation of Japanese technology is not only a source of national pride but also a reflection of the nation’s desire to overcome the horrors of the 3.11 disaster. In the face of global catastrophe, the film suggests that Japan can stand as a beacon of scientific innovation and responsible stewardship of technology (Mihic 92).

Moreover, Shin Godzilla goes beyond showcasing the brilliance of Japanese scientists and extends its focus to the resilience of ordinary Japanese citizens. The film’s heroes are not superhuman beings but rather bureaucrats, chemical engineers, plant workers, firefighters, and administrative assistants who work tirelessly to save their nation. This portrayal of average workers as the backbone of resilience resonates with a generation known as the “corporate livestock” who grew up in the economic downturn of the 1990s and 2000s (Mihic 98). The film emphasizes collective effort and teamwork, highlighting that no sole individual has the power nor responsibility to save the day, which contrasts the original 1954 film, in which Dr. Serizawa takes the full brunt of his responsibility as the inventor of the Oxygen Destroyer and the repercussions that come with its usage as a weapon against Godzilla. This reflects a Japan where the sense of responsibility and dedication to one’s job takes precedence over personal relationships and individual achievements, especially during times of crisis (Mihic 99).

The film also provides commentary on generational shifts within Japanese society. The older generation, often depicted as inept and slow to adapt to change, is symbolically eliminated during Godzilla’s rampage, allowing the younger generation to take center stage and showcase their capabilities. This is especially evident in the film’s elimination of the former Prime Minister and six Japanese ministers as they were killed off before the climax of the film and did not make the more major decisions. The film’s portrayal of the shachiku–corporate livestock–as highly competent, hardworking individuals who are restrained by older generations resonates with those who came of age during Japan’s economic downturn (Mihic 100). The film’s romanticization of self-sacrifice for one’s country, as seen in the dedication of SDF personnel and government officials, further emphasizes the importance of working together as a nation in times of crisis and highlights the collective spirit that defines Japan (Mihic 101).

Shin Godzilla not only resonates with its immediate post-3.11 context but also finds profound continuity with Hideaki Anno’s earlier work, Neon Genesis Evangelion. Both are meditations on catastrophe, institutional paralysis, and individual agency—and they are sonically intertwined through the music of Shirō Sagisu. Tracks like “Decisive Battle” and “Famously” are deployed across both works to underscore moments of existential pressure and moral ambiguity, linking the internal apocalypse of Evangelion with the external national trauma of Shin Godzilla (Mihic 97). This musical mirroring is not superficial; it reflects how Anno reuses emotional architecture to comment on different but connected crises of belief, authority, and action. The film’s use of “Yashiori sakusen” (Yashiori Strategy) directly echoes Evangelion’s “Yashima sakusen,” and in both instances, these operations represent collective action in the face of overwhelming threat. As Mihic notes, Evangelion fans even referenced “Yashima” as a rallying cry during energy-saving efforts after 3.11. In both narratives, we witness characters pushed beyond personal reluctance and institutional rigidity—Shinji in his cockpit, Yaguchi in his war room—mirroring Japan’s fraught relationship with nuclear power and its entangled legacy of technological advancement and national trauma.

The 2017 live orchestral album Shin Godzilla vs. Evangelion Symphony crystallizes this shared cultural and emotional landscape. Performed by the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra and scored by Sagisu with homage to Akira Ifukube, the concert reimagines both soundtracks as part of a singular narrative of disaster and renewal. This album underscores how, though separated by decades, these works speak to the same wounded psyche and the same generational fear: that our institutions will fail us, but maybe we won’t fail each other.

The thematic parallels between Shin Godzilla and Evangelion extend beyond music and into the psychological and sociopolitical terrain of their characters. Both stories reflect issues that are culturally specific to Japan: “the increasing distrust and alienation between the generations, the complicated role of childhood, and, most significantly, a privileging of the feminine” (Napier 424). For instance, Shinji’s self-sacrificial charging towards the angel when Misato defies NERV protocol to order him to enter the cockpit during the series, which echo World War II kamikaze pilots who rammed their planes into enemy ships out of “…a complex mixture of the times they lived in, Japan’s ancient warrior tradition, societal pressure, economic necessity, and sheer desperation” (Powers, cited by Dejeu 16). In Shin Godzilla, this same kamikaze ethos is updated through figures like Yaguchi and the “misfit” task force who, unlike the self-mythologizing heroes of older wartime narratives, work not out of nationalism but out of duty, logic, and care. Anno is not romanticizing technocracy or bureaucracy, but imagining what might happen if ordinary, empathetic people actually ran things. The idea is not revolution, but repair.

This is also reflected in characterization: Hiromi Ogashira, who evokes Rei Ayanami’s quiet brilliance, and Kayoko Ann Patterson, a confident diplomat reminiscent of Asuka Langley, both bring a generational and gendered counterweight to the political old guard. Unlike Evangelion’s surreal landscapes, Shin Godzilla roots its apocalypse in the mundane: meetings, protocols, acronyms. And yet both works arrive at a similar proposition as the EVA and Godzilla are “essentially anthropomorphized, a concrete Other that is, initially at least, a necessary part of the characters’ identities” (Napier 430). They are anthropomorphized as projections of societal anxiety, cultural memory, and the limits of human control. These connections highlight the enduring themes in Hideaki Anno’s oeuvre, providing viewers with a new lens through which to appreciate both of his works.

The ending of Shin Godzilla is deliberately opaque. Whether seen as a fantastical outcome or a reflection on the potential for Japan’s resurgence, the film allows viewers to engage with its narrative on various levels. The cryptic message left by the disgraced professor Goro Maki, “I did as I pleased. Do whatever you want,” encourages diverse interpretations, ensuring that the film remains a point of discussion and reflection (Mihic 102). Shin Godzilla (2016) emerges as a poignant reflection on Japan’s resilience and cultural identity in the wake of the 3.11 triple disaster. Whether we read Godzilla’s frozen form as a hopeful resolution or a suspended threat, the film leaves us with a powerful image of collective effort halting the unthinkable. It is not an endorsement of how things are, but rather a fantasy of how things could work if the system functioned not through hierarchy, but through trust, adaptation, and mutual belief. Shin Godzilla is a mirror for any society negotiating crisis, fear, and the future. In a world increasingly defined by catastrophe, it asks not just whether we can survive, but who we become in the process of trying.

Works Cited

Dejeu, Vanna. “Thematic Tension between Trauma and Triumph in Hideaki Anno’s Neon Genesis Evangelion.” Honors Senior Theses/Projects, 91, Western Oregon University, 1 June 2016.

“Fukushima Disaster: What Happened at the Nuclear Plant?” BBC News, BBC, 23 Aug. 2023, www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-56252695.

Mihic, Tamaki. “(STILL) COOL JAPAN.” Re-Imagining Japan after Fukushima, ANU Press, 2020, pp. 87–116. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv103xdt4.10.

Napier, Susan J. “When the Machines Stop: Fantasy, Reality, and Terminal Identity in ‘Neon Genesis Evangelion’ and ‘Serial Experiments Lain.’” Science Fiction Studies, vol. 29, no. 3, 2002, pp. 418–35. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4241108.

Shin Godzilla (シン・ゴジラ). Directed by Hideaki Anno, Toho Co., LTD., 2016.

Leave a comment